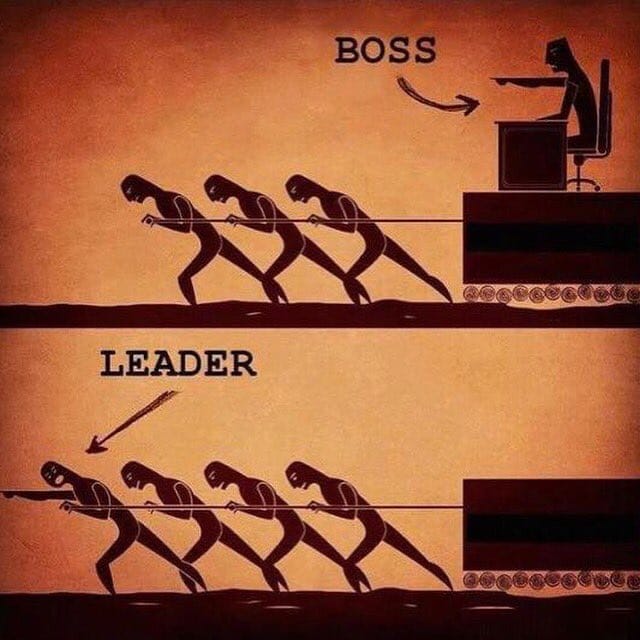

If I had to bet on which graphical meme appears most frequently in my LinkedIn timeline, I'd say it's the one about "servant leadership". I'm sure you recall it easily (even if it comes in many "flavors" these days):

- In the first frame, you see a line of people pulling the cart with a single individual inside (it's clear that he's not pulling/pushing himself, just shouting something), labelled as "the boss"

- In the second frame, all the characters are pulling the cart together, with no one inside; the label on the first of them says: "the leader"

It doesn't matter who shares that, in what context, with what kind of punchline - the sentiment is always unequivocally positive. People love the idea of "servant leadership" - leaders who are primus inter pares (the first among equals) and not afraid to lead by example, in the trenches.

It's the moment I should admit something - each time I see this meme, it saddens me a bit. Not because I empathize with an archetype of a boss who does nothing but apply pressure. Or because I think it's beneath the leader to step down and get the shit done like everyone else around. My issue with this naive interpretation of "servant leadership" is that it has led the whole generation of leaders to commit the most common mistake a fledgling leader can commit - "getting monkeys on their shoulder".

Where's the monkey?

OK, I owe you some clarification. First of all: what monkey and what shoulder.

In 1974, Harvard Business Review published a very interesting article - "Managing Management Time: Who's Got the Monkey?". It came with a short parable (to illustrate the issue):

- An employee comes to a manager with a problem.

- The manager knows how to solve the problem, but isn't able to explain it to the subordinate in full extent, so (s)he decides to do this asynchronously ("I'll send you an example", "I'll describe how I did it previously", "I'll solve the first case myself and then let you know", "Let me check this myself first & then I'll prepare a detailed instruction for you", etc.)

- But now it's not the employee's task anymore - it's the manager who has the next (blocking) action item. So it will be the employee asking the manager whether the work is done or not ("Did you manage to do what you've promised?") — both sides have effectively swapped places: the manager is obliged to do some work for the employee (not the other way around).

But where's the monkey in all that?! Monkey is the "next move". And it's clearly on the manager's shoulder ...

A side note: yes, I did notice that the HBR article was about managers, NOT leaders (which is a big difference). Nevertheless, it changes nothing - both groups are equally susceptible to this mistake.

I'm sure I don't have to go into details on why collecting monkeys on your back is a terrible idea, so I'll be brief here: while your intentions may be stellar (to share your experience & wisdom, to support your subordinates, to contribute where it matters, to remove the impediments, etc.), it's simply NOT effective (in the majority of cases):

- Instead of developing as a leader (breaking down realistic goals, asking good questions, pushing folks slightly outside their comfort zone, delegating effectively, etc.), you rely on your existing IC skills.

- You easily become a bottleneck on a critical path (especially if you over-promise to multiple people).

- People reduced to following your "script" have limited ownership (/motivation), learn less, and become victims of a ruinous empathy (you compensate on the weakness they could have been working on)

Monkeys welcome?

Don't get me wrong - sometimes it's more than welcome to adopt a monkey or two. When so? Here are some examples:

- To make a good example (e.g., prove that something is indeed essential if even the CTO/VPE gets his hands dirty).

- To "experience the real work" - see the real issues and challenges of folks who actually do the stuff (MBWA, genba genbutsu).

- To express the cultural values visibly (show them implemented in practice, instead of preaching them theoretically)

- To expose and disarm bullshit (e.g., prove that something is indeed doable, while subordinates claim it's not) - but watch out, you may make a fool out of yourself if you're not right here!

But these should be outliers and exceptions. If you recall the delegation poker (from Management 3.0), there are 7 "flavors" of delegation there and none of them is named "just do it yourself".

The art of dodging monkeys

The original article describes the four basic steps one should use to avoid monkey adoption:

- Describe the monkey (before the assignment)

- Assign the monkey

- Insure the monkey

- Check the monkey

I believe the first two are self-explanatory (and the only thing worth emphasizing is that "describing" is the necessary investment even if its tempting to do the stuff yourself ...), so let's focus on the other two:

- "Insure the monkey" means that the leader/manager should come with a clear strategy on how they support the subordinate handling monkey (e.g., recommend then act, or act then advise)

- "Check on the monkey" is essentially a preset routine to ensure the monkey is handled correctly (e.g., sync points, milestones, regular check-ins).

But I wouldn't be myself if I didn't add a few suggestions of my own:

- Asking good questions is one of the most essential skills for every leader/manager - never stop practicing it, e.g., by driving your subordinates, not by telling them specifically what to do (that reduces the ownership), but by asking them good questions, e.g.:

- What's your real goal here?

- Does this activity contribute to the goal? How?

- Isn't there a simpler way to achieve the same goal?

- What could go wrong here? Is there a way to prevent those issues?

- What assumptions would make this bet safer/more predictable?

- Don't be a perfectionist. Yes, maybe you've done it one way in the past, but there's more than one way that is "good enough" - let your folk(s) discover and apply their way.

- Instead of specifying very detailed instructions for your folks (that are never accurate enough and always too prone to interpretation), focus on setting crystal clear success criteria ("what" instead of "how").

- Keep slicing the elephants - reduce complexity and cognitive load by breaking down goals into well-bound milestones (that appear much less overwhelming and ambiguous).

- If there's no other option and you just have to be involved, fight the temptation and share the monkey instead of handing it yourself - set up a brainstorming/pair-programming session to help the individual learn from you directly and synchronously.

And what's your opinion on this issue? Is it OK for leaders to take more/the most challenging monkeys on their shoulders? Do leaders differ from managers when it comes to monkey adoption? Do you have any proven tactics for monkey avoidance? Feel free to share in the comments below.